We have talked about it before and will likely talk about it again in the future: systemic design is deeply entwined with our vision for Pine and all our core mechanics. In this short, summarizing blog, we want to take a quick look at what it means again, how it’s becoming a trend in game design and how it helps us create the game we envision.

While the term is not ‘officially’ defined by any means, we see systemic design (which often leads to “emergent gameplay”, a term more broadly spread through marketing) as the process of setting up rules and systems that lead to scenarios, instead of designing and developing the scenarios themselves. Some examples might help.

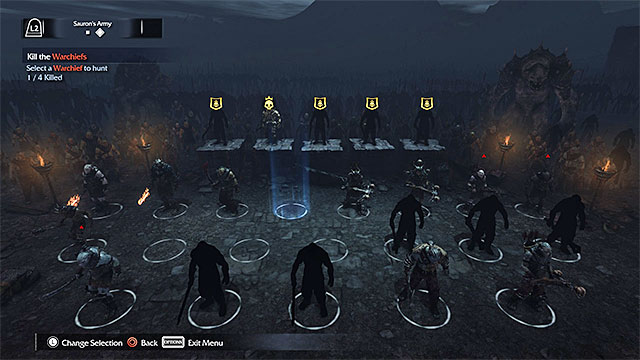

A game we often mention as inspiration is Monolith’s Middle Earth: Shadow of Mordor and its famous Nemesis system. In that, a hierarchy of Orcs in the world is presented to players. By making certain decisions in gameplay and by moving your attention towards certain Orcs, the story and your enemies can be different. The system personalizes the stories you have with these Orcs and makes them respond to it ingame.

Image from gamepressure.com

This means that instead of designing a specific Orc with a specific name and character for you to meet, they design the scenario which the systems then fill in with a certain Orc you happened to meet during your playthrough. It’s a different approach that, in the end, plays like a thought-out design, but could be different on a second playthrough.

As described in this article, eyebrows can be raised about the popularity of such systems – why aren’t more games attempting it? With Pine, we are – not literally that system of Orcs, but the idea of stories emerging from systemic design is exciting to us, and with Pine we’re hoping to achieve similar results. Based on your actions, species will perform different actions through simple ecological rules we set up, hopefully making the story feel more and more like your story as you go along.

Ubisoft is also showing interest in this systemic approach. In a 2015 Game AI conference talk by Julien Varnier, Ubisoft’s Far Cry team explains its ambitions towards building a digital ecosystem where systemic design fosters unique, interesting and fun situations for players. They use systemic design as a tool for an increased variety in the game – and to indeed create personalized anecdotes. Ubisoft is focusing their games on being anecdote factories as such: they want to drop players in a world of stories and activities, where systems define what players can find and do. More recent games, like Watch Dogs 2, see this emphasized even more – they call it a non-player-centric world, as we’ve described Pine before - and it seems to become a game development trend in general.

“We wanted the world to be non-player centric, meaning it will live without you being there.” – Danny Belanger, game director on Watch Dogs 2

Our relatively short experience with action adventure games ensured that our thoughts weren’t clouded by previous projects, so we could design Pine from the ground up and attempt something truly new. But the field of systemic design is gaining a lot of interest from all developers and increased computational power makes it more viable for smaller studios, like ours.

Another big franchise that we draw some comparison to has recently shown the power of this approach is their latest title, The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. In their developer talks, they mention the idea of multiplicative gameplay: instead of designing situations (for example, Link picks up a twig that is designed to be swung) they designed systems, rules and materials (Link can pick up and swing anything that is tagged as a ‘weapon’).

Systemic design means putting your resources to the core of mechanics, rather than to specific content you want the players to encounter. With Pine, we are doing exactly that – we fill the continuous world of Albamare with stories of its own, and let the player respond to that using the ruleset we design.

Again, simple examples might help getting the point across, such as simple situations we have outlined before. Imagine strolling through the Pollen Fields in Pine, and you encounter three Litters that have made their way to two Cariblins down the road. Instead of us placing those species there and defining that they should be doing that in that moment, we design the rules for two species encountering each other: species often wander from point A to point B, and when they spot another species nearby, they either engage or ignore each other (based on the state of the hierarchy). In this instant, they engage with one another. As a player, helping or hindering either species is an action that will influence this situation, again based on rules we design instead of on a situation we try to recognize and let the game respond to.

By employing this approach to the content of the game, we are able to create cool content by solidly designing and testing the systems behind it. It saves production time and makes playthroughs more unique!

True freedom for players is reached by allowing them to learn the rules of the game and impact the game world through them. We hope to let players respond to what’s in the world and learn the rules of the world, rather than them trying to learn what’s in a designer’s mind and solve situations by learning how a situation was probably planned out.

As mentioned, increased computational power of games is leading to more systemic approaches in games, with some developers and publishers even focusing on it completely. With Pine we’re excited to be experimenting with it in these early stages, as such increased freedom in interacting with species is turning out to be a great approach!