Now that we ourselves have a much clearer idea of the game and all its design details, we wanted to spare a moment and write about an important cross section in that design: where simulation meets action-adventure.

Simulation of Albamare

One of the pillars in Pine’s design and structure is a digital simulation of an ecology. On the island of Albamare we treat all organisms equally as we let them gather food, engage in battle with each other, grow their population and look for treasure. Their goal is power, hence they will put their efforts towards increasing that power however they can.

Power means having a large reach, which means having a big population - which equals finding ways to sustain a larger population. And that brings us to food.

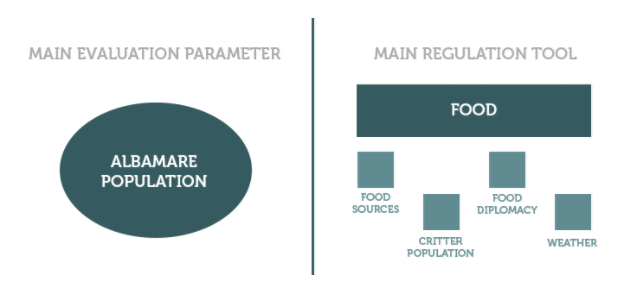

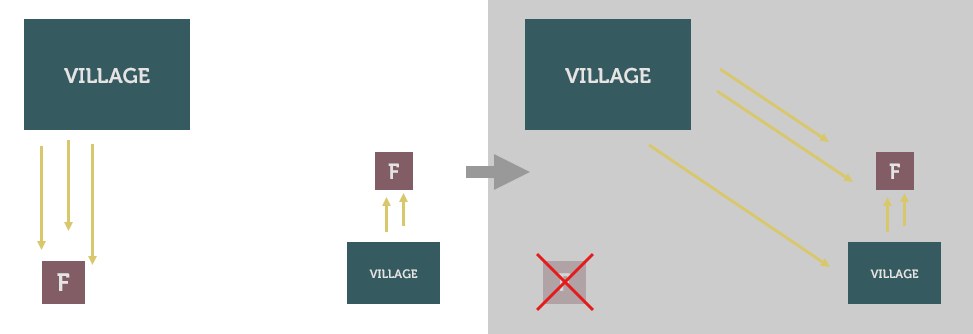

When gathered in a simple diagram, the assumption above guides to two important pillars: a main regulation device and a main evaluation parameter.

The main evaluation parameter is important: it is on the experience side for players. This value can heavily decide the pacing, structure and activity density for players. In our case, this is the population of Albamare. With 1000 organisms on the island, you’re bound to get a wholly different experience than with 100 AI actors, so it’s important to get this number right.

But then again, we don’t want to just set a number and leave it at that. The population needs to be regulated systemically to ensure it’s balanced and has some leeway to change without breaking. This is where the main regulation device comes into play: food!

Each village on Albamare has a food supply. Not just for fun - they need it to sustain their villagers, the organisms. Each species has a certain appetite - a Cariblin needs more to keep alive than a Litter, for example. This ensures we can make species very different while keeping them in balance as opposed to each other.

Food can be found all across the island: both static food sources (plants, crops) and dynamic ones (critters) ensure species have plenty of options to keep alive, as long as they move out to get it.

One more cool layer we want to mention is that species have knowledge as a resource too. They 'know' about the world, but they'll have to learn about it first. When moving out of their village, they will learn about food sources nearby and they send out scouting troops to find new food sources. They can then bring this knowledge back to the village, where it's stored, which makes finding food easier next time. Species can even trade this knowledge with each other.

Even without the player’s involvement, the species’ tasks will be performed. But obviously, as a player, you want to get involved - what can you do?

Tools in the simulation

We have three core pillars for gameplay in Pine:

- Exploration: finding villages, discovering new critters, gathering resources to create 'Ideas' with, finding special items, reaching higher vantage points, a bit of puzzling in Albamare's Vaults... Through all of this, you learn about the island and in particular about the species that live on it.

- Diplomacy: talking and trading with villages, placing 'Bounty Bills' on species to stir up the island's political relationships, moving food or food sources... All actions that create power shifts in the ecogical hierarchy or change the affection species have for you.

- Combat: Fighting your way through Albamare is also an option - although no easy feat. Organisms learn from you and, more importantly, have a lot more experience in fighting than Hue does. Better be careful!

We want every action the player does to be applicable to either of these categories to ensure a focused, well-balanced gameplay system. But under this layer of playability lies the continuous simulation, and the two need to work together.

Out of previous assumptions, we drew the logical conclusion that the player should at least be an influencing factor on the main regulation device: food. Therefore, food sources in the world are there for players to use as well: you can gather food from them and bring it to villages, you can consume it yourself, or you can destroy the food or even the whole source altogether.

Finding a food source and destroying it might have large consequences. Given the resource of knowledge for species, a certain tribe might have a nearby food source they attend to - but if you decide to move or remove that source, they will have to scout for a new source or steal food from other species.

We call that action and simulational reaction ripple reasoning. Players can figure out ways to indirectly affect the hierarchy, even though it might spiral into some unexpected results.

Of course, rather than indirectly affecting one of the knobs that defines a tribe's location or population, players can also choose to go at it directly, using combat or trading. Donating food to a village will make life easier for them, while taking it away can seriously disrupt their flow. And, using combat, attacking organisms directly can also impact a village and its status pretty permanently.

Conclusion

Designing Pine as one of the very first action adventure simulation games, we're presented with hugely interesting opportunities. The challenge lies in defining low-level, under-the-hood systems that are inherently balanced, while presenting the player with concrete, fun activities to interrupt these systems.

Pine might be exploring a new subgenre, but regardless of how you would define it, fun is the most important aspect. We want players to dive into Albamare and to come to know its intricacies, while finding out how to influence those themselves. A game doesn't have to be based all around a player - as long as they feel they have a meaningful role in the digital environment.

Stay tuned for more in this year's Fall Demo, where we hope to bring the first fully fledged slice of Albamare's simulated ecology to you!

We have talked about it before and will likely talk about it again in the future: systemic design is deeply entwined with our vision for Pine and all our core mechanics. In this short, summarizing blog, we want to take a quick look at what it means again, how it’s becoming a trend in game design and how it helps us create the game we envision.

While the term is not ‘officially’ defined by any means, we see systemic design (which often leads to “emergent gameplay”, a term more broadly spread through marketing) as the process of setting up rules and systems that lead to scenarios, instead of designing and developing the scenarios themselves. Some examples might help.

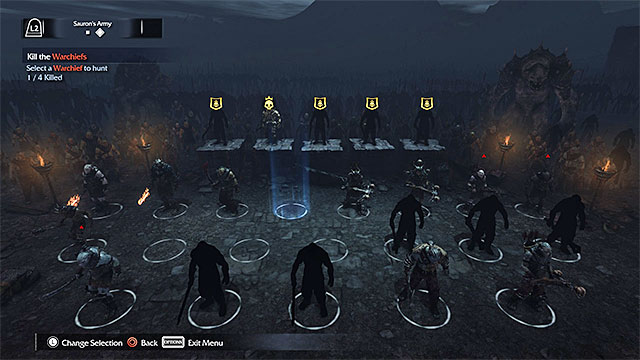

A game we often mention as inspiration is Monolith’s Middle Earth: Shadow of Mordor and its famous Nemesis system. In that, a hierarchy of Orcs in the world is presented to players. By making certain decisions in gameplay and by moving your attention towards certain Orcs, the story and your enemies can be different. The system personalizes the stories you have with these Orcs and makes them respond to it ingame.

Image from gamepressure.com

This means that instead of designing a specific Orc with a specific name and character for you to meet, they design the scenario which the systems then fill in with a certain Orc you happened to meet during your playthrough. It’s a different approach that, in the end, plays like a thought-out design, but could be different on a second playthrough.

As described in this article, eyebrows can be raised about the popularity of such systems – why aren’t more games attempting it? With Pine, we are – not literally that system of Orcs, but the idea of stories emerging from systemic design is exciting to us, and with Pine we’re hoping to achieve similar results. Based on your actions, species will perform different actions through simple ecological rules we set up, hopefully making the story feel more and more like your story as you go along.

Ubisoft is also showing interest in this systemic approach. In a 2015 Game AI conference talk by Julien Varnier, Ubisoft’s Far Cry team explains its ambitions towards building a digital ecosystem where systemic design fosters unique, interesting and fun situations for players. They use systemic design as a tool for an increased variety in the game – and to indeed create personalized anecdotes. Ubisoft is focusing their games on being anecdote factories as such: they want to drop players in a world of stories and activities, where systems define what players can find and do. More recent games, like Watch Dogs 2, see this emphasized even more – they call it a non-player-centric world, as we’ve described Pine before - and it seems to become a game development trend in general.

“We wanted the world to be non-player centric, meaning it will live without you being there.” – Danny Belanger, game director on Watch Dogs 2

Our relatively short experience with action adventure games ensured that our thoughts weren’t clouded by previous projects, so we could design Pine from the ground up and attempt something truly new. But the field of systemic design is gaining a lot of interest from all developers and increased computational power makes it more viable for smaller studios, like ours.

Another big franchise that we draw some comparison to has recently shown the power of this approach is their latest title, The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. In their developer talks, they mention the idea of multiplicative gameplay: instead of designing situations (for example, Link picks up a twig that is designed to be swung) they designed systems, rules and materials (Link can pick up and swing anything that is tagged as a ‘weapon’).

Systemic design means putting your resources to the core of mechanics, rather than to specific content you want the players to encounter. With Pine, we are doing exactly that – we fill the continuous world of Albamare with stories of its own, and let the player respond to that using the ruleset we design.

Again, simple examples might help getting the point across, such as simple situations we have outlined before. Imagine strolling through the Pollen Fields in Pine, and you encounter three Litters that have made their way to two Cariblins down the road. Instead of us placing those species there and defining that they should be doing that in that moment, we design the rules for two species encountering each other: species often wander from point A to point B, and when they spot another species nearby, they either engage or ignore each other (based on the state of the hierarchy). In this instant, they engage with one another. As a player, helping or hindering either species is an action that will influence this situation, again based on rules we design instead of on a situation we try to recognize and let the game respond to.

By employing this approach to the content of the game, we are able to create cool content by solidly designing and testing the systems behind it. It saves production time and makes playthroughs more unique!

True freedom for players is reached by allowing them to learn the rules of the game and impact the game world through them. We hope to let players respond to what’s in the world and learn the rules of the world, rather than them trying to learn what’s in a designer’s mind and solve situations by learning how a situation was probably planned out.

As mentioned, increased computational power of games is leading to more systemic approaches in games, with some developers and publishers even focusing on it completely. With Pine we’re excited to be experimenting with it in these early stages, as such increased freedom in interacting with species is turning out to be a great approach!

Today we’re sharing a closer look at one of Albamare’s species, one that is roaming the island and… spits on everything it can see. This is the Litter!

Let’s start with the basics. The Litter is an alternatively evolved version of the lizard (Lacertilia, Reptilia) who developed particularly toxic saliva to fend off enemies and build tools with. Taking inspiration from the Knight Anole and standard Gecko, the Litter adds a bit of flair by standing, walking and running on two feet.

Those who have been with us for a while might notice that this is an updated version of the Litter model! We’ve been working hard to align their style with the newer, more detailed Fexel and Krocker species. A similar treatment was given to the Cariblin recently!

When fully clothed and evolved, the Litter can wear self-knitted clothing, like a hat or ankle- and arm-guards. Some of the more adventurous Litters even have space to hang lanterns from their hood.

The Litters collect food and resources in the large wooden baskets carried on their backs. Alongside the standard insects, they got used to eating fish, grains and berries.

It spits and spreads their acid in cases of tension and conflicts. When things get just a bit too warm for them, they tend to bite, so don’t get too close.

The Litters live and fight in groups. Even though they can’t block, they’ll make sure to work together to let you focus on one place, before hitting you in the back with a rapid spit. These little fellas can be hard to battle!

Their language is snappy and noisy, which fits their culture well – they don’t need sophisticated communication, as long as they can eat and spit.

Litters also have a knack for shiny things. They tend to decorate their housing arrangements with glittery stuff like crystals and glow-worms – now you know what to look out for to appeal to them!

Their housing arrangements are compact but useful. The more evolved they are, the more advanced their buildings become vertically – and the use of materials is pretty house-like too. Check it out!

Each species in Pine has their own musical theme – when they grow bigger and stronger on the island, you’ll hear more influences of that particular theme. We’re always looking for interesting instruments and soundscapes to underline the culture of the species.

Here is, for the first time, a sample of the March of the Litters!

In the current games landscape, small teams are often inclined to use experimental mechanics and themes, sometimes resorting to procedural systems. These systems allow for generation and creation of content based on a designed set of rules. Endless survival games and other games with repeatable gameplay loops often emphasize systems like these to express the infinite replayability and randomized or sometimes surprising content.

From a development perspective, procedural content versus 'handcrafted' or designed content is an important spectrum to look at. With teams getting smaller and gamers getting hungrier, it's important to assess and appreciate what procedural generation can do for your game.

For Pine, we've heard our gamer audience use the word 'procedural' rather often - procedural world, procedural evolution, procedural crafting. In light of the controversial releases of recent games with procedural content, of which the recent No Man's Sky is a good example, we want to share more information about Pine's "procedural" or generative systems. What exactly is the procedural aspect of Pine?

Systemic content in Pine

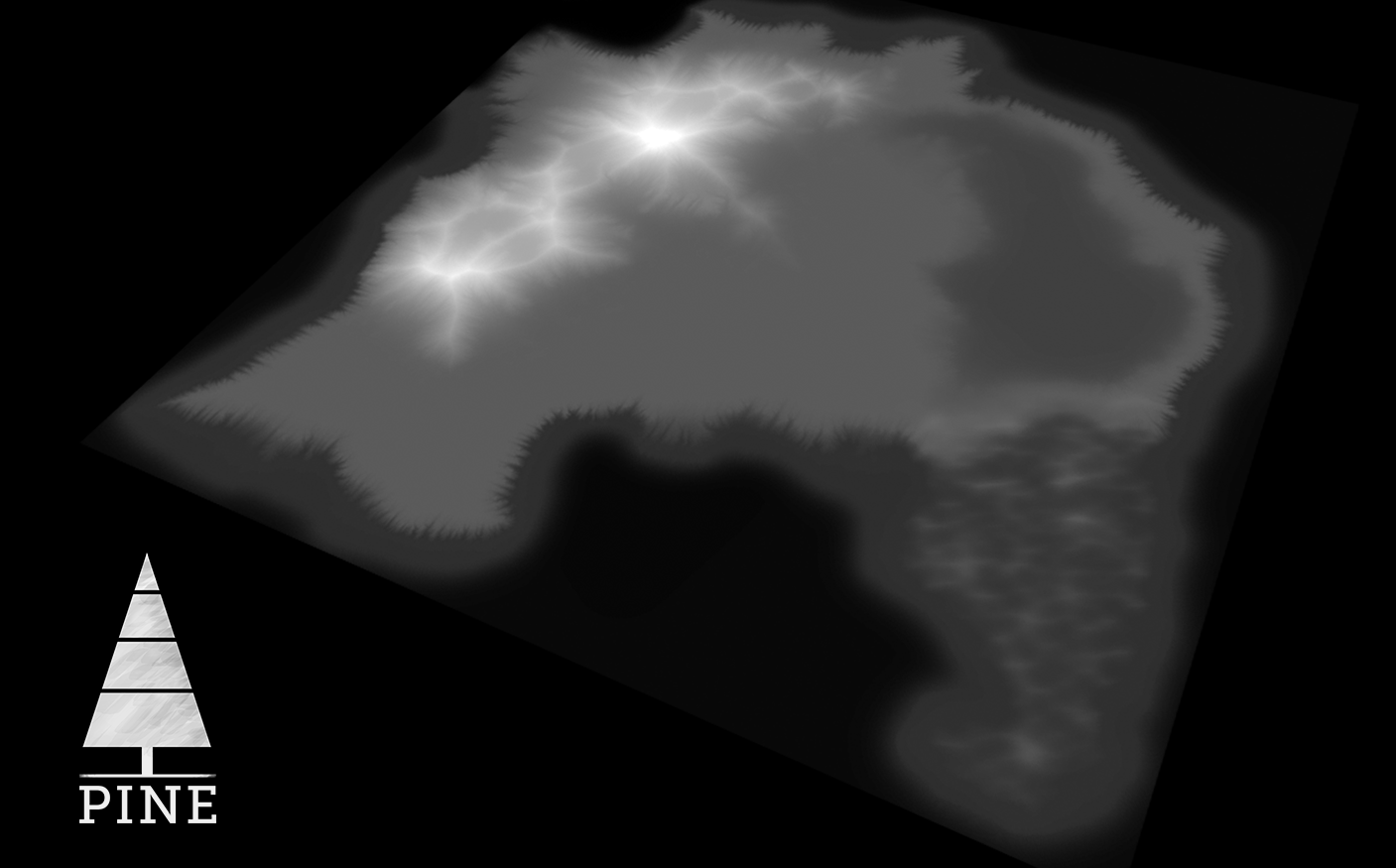

In part, we are using procedural systems in Pine to help us develop more efficiently. These are systems that go through algorithmic procedures based on a set of rules to define the content. We use this to easily create assets during development, but we do not generate any content in Pine (in realtime). Our procedures are based on something we’ve created first - in the case of the island, it’s based on a pre-defined height map.

We created a heightmap first, a black-and-white image that can be read by our terrain system.

We then generate a mesh / terrain purely out of that heightmap. This is a procedural system, but without the randomness that’s often proposed in ‘classic’ procedural generation. We do this during development, so there is only one island.

Therefore, it’s good to steer away from the classic term procedural generation right away - instead, we often talk about systemic content.

It’s very important to stress that we don’t ever let our code create content that we haven’t defined ourselves. We design systems, and we let these play out and sort themselves out using the procedures we design.

However, our evolution system is far from a fully designed experience. We don’t dictate that the game develops into a certain direction after a specific amount of time, for example. So what is it exactly?

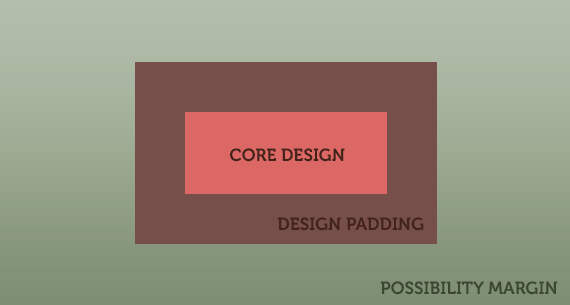

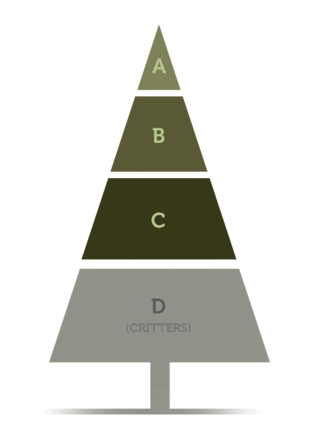

A simple box model

We often visualize it using a simple box - the game can ‘think for itself’ anywhere inside the box, but we design that area. We can easily look at it as a box with padding and margins (like in CSS):

- Core design: Creatures have a default, designed behavior, set up to be interesting within the combat we provide. We design a ‘critical path’ through the game, as being a ‘default’ experience.

- Design padding: Instead of defining that a species has 20 HP and 3 STR, we define that it can have 18-22 HP and 2-4 STR. This way, the starting situation can provide players with slightly different species, allowing for them to adapt to the ones the player is weak against.

- Possibility margin: Then, throughout the entire playthrough, these species and organisms evolve in different directions - we give them the minimum and maximum values so that they stay within the box.

For players, this means each individual organism within a species can look and act different, while all sharing the same basic behavior and culture. We set all of them up to do slightly different things and look different, based on individual personality and genes.

This model applies to everything we make - we always allow for change and adaptation, but define all the borders. This way we get a strongly designed experience that simply won’t break (never say never, but that’s the goal).

In other words, we design all of Pine - but rather than designing a static version of an enemy, we design a dynamic enemy. This way, we can populate Pine's island with dynamic species rather than the same enemy over and over again. It fits in completely with the adapting combat.

The ecological hierarchy

Players can therefore be better or worse against a certain genetic group within a species: if the more defensive personalities among organisms have a higher success rate against you, these will thrive and survive, based on natural selection. Visually, a certain color of organism might (coincidentally) be best against you, coloring their entire species more towards that hue.

This, in the end, leads to the ecological hierarchy in our game world. Players shape the populations on the island by empowering certain species and make others weaker. Species that are stronger against the player will appear more, while 'easy' species drop down, possibly even into extinction.

We visualize this in a few different ways, including their outfits. On the island, you will mostly see it in their ‘housing’. Instead of designing static locations for their living facilities, we place home sockets - points that can be filled in with any species’ home.

We can decide what type of house can stand where, so that it always looks good and handcrafted. Using rules and quota, we define how many are placed and in what combinations. Endless variety is possible, while it will always look right.

Again, we don’t generate content or procedurally create houses, but we procedurally (or systematically) place them based on a designed layout. Systemic content!

Producing a 'full' organism

For the production of our content this all means we start out with the outer box, including the padding and margin. We ask ourselves: what does a fully evolved species look like?

This is done for mostly animation and design purposes. Lukas, our animator, needs to animate for the most extreme of circumstances, so that no part of an organism's outfit clips with anything else. Design-wise, the species needs to work best when all their moves are fully 'unleashed' - because if the species has reached a high level in the ecology and thus appears more, gameplay with them should be perfectly balanced and extremely fun.

The key here is generalization. Instead of designing all these species from scratch, we spent a lot of time defining their absolute core, so that we could systematically figure out what we needed for each. We can make 12 completely different species, but first we boiled them down to their core.

Conclusion

So, rather than using procedurality to generate, we use it to amend. We believe strong content comes from well-thought out design, and if we would build a large framework that we could never test, being the small team we are, the results can be unpredictable and messy.

Our goal from the start was to design a solid base structure that could then be systemically amended and adapted to players. Even if players would do nothing or play exactly the same every time, the game should not break - because the game has a 'default' response for everything. But on top of that is a layer of content adaptation that is dynamic towards what players do, to make Pine listen to players as best as possible.

By not procedurally generating anything, we also keep full control over everything. The vision is to make Pine fantastic through memorable moments that emerge from systematic content.